Malcolm Miller’s review of the London marathon for ‘Musical Opinion’:

“To listen to and enjoy the complete cycle of Beethoven piano sonatas in a single day is a both a rare treat and a challenge of concentration; to perform them is all the more so. Julian Jacobson’s Beethoven Marathon, held in the ambient surrounds of St John’s Church, Waterloo on 12 November 2022 was a phenomenal feat of pianistic prowess, memory, and sheer stamina….At times, the piano’s sound reminded one of the indubitably unique Beethovenian ‘klang’ associated with great masters of the past such as Kempff, Schnabel or Serkin….”

Read the whole review here.

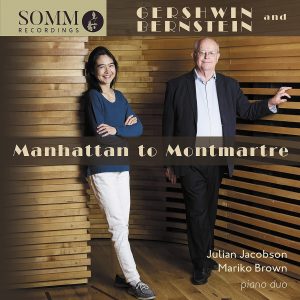

Bernstein Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, Gershwin Second Rhapsody, An American in Paris, Rhapsody in Blue; Julian Jacobson, Mariko Brown; SOMM

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on 23 February 2022 Star rating: 4.0 (★★★★) on his website https://www.planethugill.com/2022/02/mm.html

Classic American pieces that cross over between jazz and classical come up delightfully sparkling in these transcriptions for two pianists

Transcribing music for two pianists (whether at one or two pianos) can often bring new insights, shorn of the brilliance and colour of the orchestration, the work’s bones are often seen better and can place the piece in new light. On this disc from SOMM, Manhattan to Montmartre, pianists Julian Jacobson and Mariko Brown perform duet transcriptions of four iconic works, Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, and three works by George Gershwin, Second Rhapsody, An American in Paris and Rhapsody in Blue. The Bernstein was transcribed for two pianos by American composer John Musto in 1998. Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody, and An American in Paris were transcribed for piano duet by Julian Jacobson in 2014 and 2016 respectively, whilst Rhapsody in Blue was transcribed for piano duet by Henry Levine in 1925, a version that Gershwin used to play with friends.

In 1910, more than three-quarters of the population of New York were either immigrants or the children of immigrants, so no wonder the city’s musical culture developed as such a melting pot, combining music from European homelands with African American music and more. Irving Berlin was born in Russia, Vernon Duke was originally Vladimir Dukelsky, George Gershwin was the son of immigrants from Russia, Richard Rodger’s grandparents were Russian immigrants whilst Leonard Bernstein’s parents were from the Ukraine [I am indebted to Robert Matthew-Walker’s admirable booklet note for this fascinating information]. Additional to this Russian factor should be added that many (if not all) these immigrants were of Jewish origins, the Russian pogroms against the Jews in the late-19th and early 20th centuries causing significant problems.

The sense of musical hybridisation, the creation of new strains by combining existing ones, was palpable and of course, it continued on a multiple levels. So that George Gershwin, having mastered Tin Pan Alley and the Broadway via a genre that modern research suggests owes rather a lot of Klezmer, moved to reabsorb the 20th century classical idiom. With transcriptions for piano, we no longer have to worry about whether we should be listening to Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue in its original jazz-band orchestration by Ferde Grofé or in the later symphonic version. The Second Rhapsody and An American in Paris would be premiered in Gershwin’s own orchestrations and there is evidence to suggest that he was intending to do his own orchestral version of Rhapsody in Blue.

The disc begins, however with Bernstein, his symphonic suite based on the music from the musical. West Side Story debuted in 1957 and Bernstein created the Symphonic Dances for the New York Philharmonic, which premiered the work in 1961. This is far more then simple greatest hits, it is a 20 minute sequence that effectively tells the story in music, with writing for orchestra that is more complex than Bernstein might consider for a stage musical.

Besides having individual solo careers, Julian Jacobson and Mariko Brown have been playing as a piano duo since 2011 and it shows. The bring a sense of unanimity of purpose and clarity to this music. There is a lovely rhythmic snap to their Bernstein, along with a sense of relishing the complex textures and the drama. There is plenty of lyric beauty here, but what we constantly notice is Bernstein’s relishing of complexity of texture, rarely are there melodies with a simple oom-pah rhythm accompaniment. We have come a long way from Tin Pan Alley of the early 20th century. And of course, the short finale is devastating and far from a traditional musical.

Gershwin regarded his Second Rhapsody as the finest thing he had written, but it rarely gets proper attention. It lacks the dazzle of the earlier rhapsody and perhaps the panache. You don’t quite come out humming the tunes, but as a musical work it is more sophisticated and stronger than the earlier music. This strength comes out in Jacobson’s transcription, without the brilliance and colours of the orchestra (though the two pianists demonstrate their own wide range of colours) we get a sense of the work’s complex textures and remarkably mid-century musical style. Jacobson and Brown make the rhapsody seem less jazzy, and more akin to the music in Europe that Gershwin was listening to – Stravinsky, Ravel and perhaps even Bartok.

Whilst Gershwin’s An American in Paris was all his own work (after Rhapsody in Blue, he did the orchestrations of his Concerto in F and American in Paris himself), Gershwin still composed at the piano and it is this factor that probably lends the work to transcription. Gershwin wasn’t alone in this, Stravinsky’s own piano four-hands versions of his early ballets have developed come currency and these were not arrangements but initial versions. Again the rhythmic alertness of the playing delights, along with the way the two players mesh together so that fragments emerge from the textures and disappear, reflecting the colours of the original orchestra. This is a performance that puts a real smile on the face.

Finally we reach Rhapsody in Blue. Full of rhythmic verve and a remarkable range of colours, there is a nice swing to the music yet it clearly is not jazz. The transcription brings out the Rhapsody’s remarkable bones, and both Jacobson and Brown have the time of their lives with the music, managing to be fun and complex.

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), transc. John Musto, 1998 – Symphonic Dances from West Side Story [21:52]

George Gershwin (1898-1937), transc. Julian Jacobson, 2014 – Second Rhapsody [15:03]

George Gershwin, transc. Julian Jacobson, 2016 – An American in Paris

George Gershwin, transc. Henry Levine, 1925 – Rhapsody in Blue

Julian Jacobson (piano)

Mariko Brown (piano)

SOMM SOMMCD 0635 1CD [72.30]

Buy the CD here: https://www.somm-recordings.com/recording/manhattan-to-montmartre/

Listen below on Spotify:

Pre-Valentineʼs Day Concert – Julian Jacobson at St Jamesʼs Piccadilly – Mozart, Schumann, Scriabin, Prokofiev

Friday, February 13, 2015

That Julian Jacobson is one of the finest living British pianists is known to many musicians and music-lovers, and it was encouraging to see a number of other pianists in the audience for this eve of Valentineʼs Day recital, given in association with Drunken Dairy – “booze infused ice creams” and on sale during the interval. The proximity to the day of all lovers provided a convenient

tag on which to hang Jacobsonʼs programme, but there would appear to have been little in the way of musique dʼamour in the pianistʼs selection. No matter: the spectators had come to hear a fine musician in great music.

Beginning with Mozartʼs K455 Variations, a set which ranges widely in terms of emotional expression (from dainty decoration to deeper profundities, before returning a smile to the listenerʼs face in the coda), Jacobson produced a well-nigh ideal account – full of character and outstanding musical phrasing. Schumannʼs Fantasy followed almost immediately, and before many bars had been heard it was clear that Jacobson had the full measure of this masterpiece: this was an astonishingly fine account, rich in tonal variety

and depth of perception, subtle and commanding by turns – another almost perfect performance that revealed the composerʼs full genius.

The Russian second half opened with three relatively brief Scriabin pieces: well chosen for their diversity and (all things

considered) emotional scope, before a remarkable account of Prokofievʼs still-problematic Sixth Piano Sonata – problematic for the pianist in melding the sudden changes, of mood and initially uncertain melodic outline, into a coherent whole. This work, the first of the trilogy that came to be known as the ʻWar Sonatasʼ, is highly personal, more intense and inward-looking, and therefore presenting considerable interpretative decisions for a pianist who would undertake it. Jacobson was totally at one with this demanding

masterwork, producing a reading that was fully coherent, wide-ranging, but never allowed to become diffuse.

This programme was delivered by an outstanding artist. We should be so lucky.

Reviewed by Robert Matthew-Walker

Complete Beethoven Piano Sonata Cycle Nov 2011 – April 2012

Quite Superb”…from a review in Music and Vision of the third concert on Dec 7, 2011

The pianist reappeared, fresh from the fray, for the final work on his programme — the ever popular and highly respected Sonata No 23 in F minor, Op 57, Appassionata. His performance was quite superb, with perfect pacing, and those pregnant pauses, that ‘make’ or ‘mar’ all interpretations, superbly judged. The drama and poetry also included just the right amount of pathos — complete with all the slight pauses and mood changes, including various modulations, where the performer has to slightly adjust his metre. The repeated notes and trills — particularly at the close — had pristine clarity, while the Adagio chords, together with the Più Allegro, immediately beforehand, were wonderfully judged.

As Kathryn Stott once reminded me, the second movement should not be too slow: Andante con moto, piano e dolce (legato) clearly indicates a constant flow throughout each variation of the main theme. This was admirable, as were the timings of pause markings, and the fortissimo chords that link with the start of the finale, Allegro, ma non troppo. Along with the repeat, this was a thrilling experience, the closing Presto passage categorising a high water mark in any pianist’s award for excellence.

Read a review of Julian’s 2003 Charity Beethoven Marathon in London

On Friday 31st October 2003, London witnessed a memorable event: the performance by Professor Julian Jacobson of all Beethoven Piano Sonatas in one day. The place was St James Church Piccadilly, a splendid 18th Century building, its classic architecture providing a fitting setting. The recital began at 9.15am and concluded at 10pm with only three short breaks. The Sonatas were played in chronological order. Before the recital, one wondered how it would be possible to do justice to the whole oeuvre in one day. In the event, we were given a magnificent recital, an unforgettable experience. Professor Jacobson played the whole cycle from memory, only having the assistance of a score in the Hammerklavier Sonata: a feat in itself, particularly remarkable as the performance was without any memory lapses or faulty turns. A Bösendorfer grand with magnificent tone was the instrument, its bass notes particularly rich and resonating.

The afternoon section concluded at 6pm with a thrilling performance of the Appassionata, which brought the audience to its feet, the concluding Presto marking a culminating point. After a short pause the evening recital began at 6.30pm with op.78, in which Professor Jacobson again set the scene for all that followed in his mastery of tempi, dynamics and phrasing. The late Sonatas unfolded their glory, the slow movement of the Hammerklavier beautifully sustained. So it was that finally we reached the Arietta of op.111, played before an audience rapt and moved: it seemed that we listened to Beethoven’s own summary of his achievement. As the last note was played, we heard the chimes of the hour. Time brought to an end a day when Beethoven’s music through Professor Jacobson’s playing marked a memorable moment in our lives.

Over all was the “sanfter Flügel” of joy in charity. The event was in support of Water Aid, an international charity which raises money to help some of the poorest countries in Africa and other areas to have access to clean water and its related blessings. Professor Jacobson and all involved in the event gave their services free and all money rasied through donations and ticket sales was donated to the cause. We can be sure that the Master approved.

Professor Adrian Sterling, November 2003, London

Orchestra Platform Seven Debut Concert with Ivry Gitlis Feb 2012

Review from www.classicalsource.com

This debut concert for Orchestra Platform Seven (named after the “imaginary, speculative and idealised space for the weary traveller that is the ‘missing’ platform at London Bridge station) was an event for its musicians anyway, but the appearance of Ivry Gitlis, who, in his ninetieth year, proved an energised performer, added a frisson to proceedings. It will be a remarkable story for the musicians – all graduates from the Royal College of Music – to tell in the decades to come: that they played with Gitlis, who was himself taught by George Enescu (1881-1955).

Ivry Gitlis offered Chausson’s wonderfully atmospheric Poème, which concerns the unrequited love of a musician for a beautiful girl, and, after a false start – Gitlis halted proceedings after his opening statement because he was missing the cushion for his violin: “a violin without a cushion, fine, but what’s a cushion without a violin?” he entertained as one was found – gave a free-spirited account. In fact, it was the orchestra that was Gitlis’s cushion: its playing haunting and mystical – superb – to his independent voice. Much-reduced forces were employed for the Adagio from J. S. Bach’s E major Violin Concerto, which Gitlis led. It was a thoughtful meditation from the orchestra, often beautifully sounded. Gitlis the fiddle player was on show, and whilst his instrument’s tone was not rounded, his flowing phrases and long experience were sufficient reward.

Encores were inevitable (and the funny stories were an unexpected pleasure), and three were duly dispatched, with Jacobson accompanying. A heartfelt account of Maria Theresia von Paradies’s Sicilienne

preceded two by the “love of all violinists”, Fritz Kreisler: Schön Rosmarin found Gitlis full of joy, whilst he truly revelled in the dexterity needed for Syncopation. It would be remiss not to mention Gitlis’s instrument, which did not sound well, and there were other failings, but Gitlis is a player born out of a tradition of playing much freer than current audiences are used to; it was a welcome privilege to hear this legendary artist, who is a window on such practice.

Julian Jacobson opened the concert with Mozart’s C minor Fantasia, its beauty and volatility well-judged

on this church’s expressive Fazioli instrument. His unforced playing seduced and the vigorous sections were propelled. Similarly K453 was a tonic. Some beguilingly elegant oboe contributions along with the clean sounds of the strings made this a pleasure to hear against Jacobson’s refined playing.

The slow movement had an affecting stridency in places, and the finale, sprightly and flowing, unafraid of fleeting darkness, revealed both grandeur and humour, with deft touches from the soloist.

Ensemble

“Not only a remarkable achievement of stamina, memory and dexterity, Julian Jacobson’s Beethoven Marathon – a performance of all Beethoven’s thirty two piano sonatas in a single day – was also exhilarating, if slightly eccentric, artistic experience, for both performer and audience.” – Malcolm Miller

Pianist Magazine

Dvorák – Humoresques, Meridian CDE 84521

“…Jacobson’s advocacy of this music in his playing – supported by his warm defence in the liner notes – reveals many beauties, and listened to in twos and threes rather than right through as a sequence, these are often delightful pieces….Jacobson’s unfailing sense of dancing rhythm keeps them on the move – and comes into its own in the Humoresques” – Calum MacDonald

CD Review

Weber Piano Sonatas 2 & 3, Meridian CDE 84251

“This is played in an exciting and committed manner, with lots of dash and elan….Jacobson plays the ‘Invitation to the Dance’ with tremendous sensitivity and care” – Murray McLachlan

Hampstead and Highgate Express

“Julian Jacobson’s performance of Anton Rubinstein’s E flat Romance was poised and thoroughly romantic. From the restless themes of the opening movement of the Brahms, through the soft sonorities of the intermezzo, to the triumphant conclusion of the andante and wild exuberance of the finale with its Hungarian gipsy music, Jacobson majestically impelled the work along” – D.S

Dimineata Magazine, April 2005

“In his role as soloist in Chopin’s Concerto no 2 for piano and orchestra, accompanied by the George Enescu Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Florentin Mihaescu, Julian Jacobson imposed himself through his instrumental fervour, and elevated understanding of the inner musical world, his sensitivity throughout the score, his exceptional musicality and his virtuosity of great clarity and precision.”

British Music Society News

English Violin Sonatas CD Portrait – PCL2105

“All praise then to Julian Jacobson whose intelligent and spirited playing make him one of the best two or three pianists who have consistently dedicated themselves to British contemporary music.” – Robin Freeman

Western Mail

“Pianist Julian Jacobson easily matched the whole ensemble’s faultless performance of Stockhausen’s ‘Kontra-Punkte’, and a gripping rendition of Messiaen’s Cantéyodjayâ for solo piano.” – Rhodri Clark

Daily Telegraph

“A disarming technique coupled with a undoubted intellectual mastery made Julian Jacobson’s recital an awe-inspiring experience…”

“Opening his Wigmore Hall recital with a performance of Mozart’s Sonata K.576 that combined delicacy of touch with tensile strength in rhythm and structural outline. Julian Jacobson went on to cover a wide stylistic field with equal vigour…”

“He played the studies with enormous verve and with an amazing clarity, just as the rest of his programme (Schubert and Debussy) showed a carefully controlled but sensitive temperament… in Jacobson’s performance it was the verve and flair he brought to Ligeti’s textual intricacies which gave the music its particular impulse and excitement. (British premiere of Ligeti’s Etudes Book 1)…”

“(Corey Field’s Piano Sonata) a mark of the most concentrated yet imaginative resource, played with an impressive commitment, brilliance and affection…” – Bryce Morrison

Guardian

Real poise, delicacy of touch and judicious pedalling… stylish and enchanting

(Debussy’s Preludes Book 2)…”

“Julian Jacobson, in stylish and idiomatic fashion, delivered the important concertante piano part with immense brio; the orchestra complementing his efforts in a brilliantly successful account. (Martinu’s ‘Sinfonietta Giocosa’ with the Bournemouth Sinfonietta under Tamas Vasary)…”

Times

“Its near minimalistic repetitions and driving amplifications have a cunningly kinetic effect which Julian Jacobson and the English Chamber Orchestra recreated in all their brittle brilliance.

(Britten’s ‘Young Apollo’ at the Royal Festival Hall…”

Penguin Guide to Compact Discs, Cassettes and LPs

“Brillantly nimble and felicitous… he contributes a rare sparkle to the proceedings…”

Musical Opinion

“(Ravel Series). Jacobson continue to demonstrate his talent for bringing out the music’s cardinal features yet integrating them with their surrounding textures. All in all, two estimable concerts; faithful to Ravel and worthy of his memory…”

György Kurtág

“Julian Jacobson is a possessor of perfection in musical interpretation and this illuminates his chamber music partners as well as his students and all listeners…”

South Wales Echo

“Pianist Julian Jacobson was a pretty arresting performer, most notably in Messiaen’s Cantéyodjayâ, a performance packed with energy.”

Peter Feuchtwanger, EPTA UK

“He is certainly one of the most remarkable, original and interesting pianists of today…”

The Oxford Times

“It was quite clear from his recital….that the pianist Julian Jacobson is a musician to be reckoned with; an artist whose formidable interpretative power constantly reveals the known repertoire of sonatas by Haydn and Chopin in a clearer, penetrating and often revelatory light.”

St John’s College Oxford

“…hoc autem anno Julianus Jacobson multorum aures modis Beethovenii non semel sed octies oblectavit.” – Beethoven Sonata Cycle 1996